Lecture notes: International law

What is international law?

Or “public international law”

- a set of legal rules, norms, and standards that govern the relations between nations, international organizations, and, in some cases, individuals.

- seeks to create a framework for peaceful cooperation, the resolution of disputes, and the protection of human rights and the environment

Different categories, including:

Treaty law

- treaties or international agreements are legally binding contracts between states or international organizations that establish mutual rights and obligations

- bilateral or multilateral

Customary international law:

- from the consistent and general practice of states, followed out of a sense of legal obligation

- recognized as binding on all states, even those that have not explicitly agreed to them

General principles of law:

- fundamental legal principles common to the legal systems of most nations

- good faith, equity

Judicial decisions — in international courts etc.

- also form a basis of law

IR theory and international law

- your view of the law depends on your view of international relations

Realists

- international law makes no sense at all

- “this is something that only Liberals and Europeans believe in”

- “real men follow no laws”

Cf. Romantic heroes — the whole point is that they break the law — Arnold Schwartzenegger doesn’t stop at red lights

- cf. W. Bush and torture in Iraq

- “enhanced investigation techniques”

Fundamental problem:

- there is no state above the states

- according to this view — all law is made by a sovereign will

- backed up by power — by the state’s monopoly on the legitimate exercise of violence

- cf. Turkey

Natural law

Until the end of the 18th century

- natural law was the predominant way to think about international law

Medieval Europe

- within Europe — canon law, a legacy from Rome — and the law of the feudal lord

- and lot’s of customary law too

Problem: how to relate to those who were not a part of the system?

- Jews within European societies

- Muslims outside of them

Acute issue once the Europeans started making war

- Crusades to the “Holy Land”

Right to make war

- Christians could not kill each other

- but could you kill those who did not believe in the Christian God?

- can you convert them by force, etc?

Ius gentium — the “law of the peoples”

- natural law provides an answer

- does not presuppose a common religious framework

Even more acute problem: a “new world” across the Atlantic

- the people were not Christian — and maybe not even human

What rights did the Europeans have?

- with what right could the Europeans make war on them?

- could they convert them?

- could they take their land?

Curious that these issues are defined in terms of law

- this is a legalistic way of thinking — which “rights” that belong to us

International law in Salamanca in Spain

The first international lawyers were Spaniards

- are there rights given to us by nature?

- not by God, but by nature?

- the law of reason

- often associated with “the Philosopher” — that is, Aristotle

The right to life

- not to take other people’s lives

- the right to defend one’s own life

The right to work

- to trade

- to move around freely

One conclusion:

- the Indians could not stop the Europeans from preaching the gospel

- but it was probably not right to take their land

Reason vs. faith

- much discussed in Muslim tradition as well

- Aristotle was translated via Arabic into Latin

Caliphate of Cordoba

- Ibn Rushd — reason vs. belief

- Aristotle vs. the Qu’ran

If God can do whatever he lies

- can he make 2 plus 2 into 5?

Bartolomé de las Casas

- bishop in Central America

- upset about the abuses he saw around him

- starts to collect evidence against the Spaniards

- returns to Spain in order to report the atrocities to the Spanish king

Disputation in Valladolid, 1550-1551

- a debate held to discuss the treatment of the indigenous peoples of the Americas by Spanish colonizers

But never actually in one room

- rather an exchange of legal correspondence

The issue at stake

- the legitimacy of the Spanish conquest

- the moral and legal rights of the indigenous peoples

Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda, a theologian and philosopher, argued in favor of the Spanish conquest

- indigenous peoples were “natural slaves” who were inferior to Europeans

- references to Aristotle

- conquest was necessary to bring Christianity and civilization to the natives

Bartolomé de las Casas defended the rights and dignity of the indigenous people

- they were rational beings

- capable of self-governance and deserving of the same rights as Europeans

- emphasized the violence and atrocities committed by the Spanish

- advocated peaceful conversion and just treatment of the native populations

Inconclusive outcome, but important moment in the history of human rights

- influenced future discussions on the rights of indigenous peoples and colonial subjects

Natural law took indigenous people seriously

- it did give them rights

- even if the rights were ignored in practice …

Islamic international law

Siyaar

- governs relations between Islamic states and their interactions with non-Islamic states

Sources

- Quran and the teachings and practices of the Prophet Muhammad

- interpretations and rulings of Islamic scholars

Diplomatic relations

- recognizes the importance of diplomatic relations

- outlines rules for diplomatic conduct

- ambassadors and envoys are granted diplomatic immunity

Treaties and agreements:

- acknowledges the validity of treaties and agreements between Islamic states and non-Islamic states.

Islamic states

- expected to honor their treaty commitments and uphold the principles of justice, fairness, and good faith in their dealings with other states

Conduct of war:

- the importance of proportionality, necessity

- distinction between combatants and non-combatants

- prohibits acts of aggression and the targeting of civilians, religious institutions, or infrastructure vital to the civilian population

Treatment of non-Muslims:

- rights and responsibilities of non-Muslims living in Islamic territories — dhimmis

- granted protection of their lives, property, and religious freedom in exchange for paying a tax — jizya

- Islamic states are expected to treat dhimmis with justice and respect their rights

Not clear to my how Daesh etc, could ignore this

Asylum and refuge:

- providing asylum and refuge to individuals fleeing persecution or seeking protection

- regardless of their religious or ethnic background

- cf. Turkey in relation to Syria

Hugo Grotius

- there were many other names, but he was important

Hugo Grotius, 1583 to 1645

- Dutch, but worked as a diplomat for Sweden

- one of the founders of international law

At the time of the Thirty Years War

- new codification needed due to state sovereignty

Mare liberum, “The Free Sea,” 1609

Oceans should be open to free navigation and trade for all countries

- a fundamental principle of international law

- law of the sea — be governed together

Cf. Portuguese claim to monopoly on trade in the Indian Ocean

- the Dutch wanted in on the action

God had given us different resource endowments to force us to interact with each other

- we must be allowed to trade freely

- God has divided things between parts of the world to force people to interact

- international trade was part of God’s plan

De Jure Belli ac Pacis, “On the Law of War and Peace,” 1625

Based on natural law

- universal moral principles derived from human reason and the nature of things

- existing independently of any divine or human authority

- all individuals and states are bound by it

War

- just causes for engaging in warfare

- self-defense, protection of rights, and punishment for wrongdoing

- even in war, certain moral and legal principles must be upheld

Treaties and agreements

- should be respected and honored by all parties involved

Cf. Gustavus Adolphus

- carrying Grotius’ book with him at all times

- a copy was found in his bag after his death

Why?

- the point was not that he was so moralistic

- he wanted to show that he was the kind of ruler to whom the law applied

- that is, laws of sovereign states

Natural law — cf. universal revolutionary declarations

US Declaration of Independence, 1776

- “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed,—That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.”

French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen,” 1789

- “Men are born and remain free and equal in rights. Social distinctions may be founded only upon the general good. The aim of all political association is the preservation of the natural and imprescriptible rights of man. These rights are liberty, property, security, and resistance to oppression.”

Inalienable rights that cannot be taken away by any government or authority

- popular sovereignty and the rule of law

- a people has the right to rebel against an unlawful ruler

Critique of natural law

But natural law was also questioned

- unclear what its sources were

- nature is speaking — but very softly — difficult to hear what it is saying

- different societies interpret it differently

Not at all like the laws of the state

- Roman senate, Napoleon, the king — all spoke loudly and clearly

Jeremy Bentham, end of the 18th century:

- natural law is ”nonsense upon stilts”

- instead all laws should benefit “the greatest happiness of the greatest number of people”

- a principle by which law must be radically rethought

John Austin:

- makes the same argument when it comes to international law

- similar to the Realists — all law comes from supreme authority

but there is an obvious problem

- there is no similar authority in international relations

- international law is a contradiction in terms

The role of norms

- a radical alternative

- we discussed this already …

cf. English School

- the role of conventions and precedents

Laws can grow from below

- norms and customs

- the kinds of things that we do every day

The laws of grammar

- you can try to police them

- but ultimately it’s the community of speakers that decides

- how native adult speakers can’t make grammatical mistakes

Cf. societies without states — Bull made this point

- there are conventions and norms — nothing like Hobbes’ “state of nature”

- there could be something similar in relations between states

Cf. legal system of US and UK — it is all a matter of precedent

- laws are made by judges

- the law is built case by case

This is what law students study in the end

- looking for precedents

Positive international law

This opens the possibility for another kind of international law

- positive international law

What does ”positive” mean here?

- that you study what states actually are doing

- all their actions come to form a kind of pattern

- this is the pattern that you look for when you discuss international law

A new scholarly enterprise — new generation of scholars — 19th century excitement

- systematize and standardize these patterns

- or rather: pick the most “progressive” ones

- what all “civilized” people should be prepared to agree on

Understood to be a kind of science

- a law based on descriptions of the world

International conventions

- meet to compile various conventions

- starts in the 1870s

Meetings in The Hague, Paris, Geneva

- famous Geneva conventions on the laws of war

Laws of war

There are medieval precedents here:

- St.Augustine, Thomas Aquinas

- but they were based on natural law

Seriously updated by international lawyers in the 19th century

Ius ad bellum, “law on the use of force”

The legal principles that govern the legitimate use of force by states

- when a state may resort to armed force and under what conditions it is justified

Self-defense:

- A state may use force in response to an armed attack against it.

UN authorization:

- the Security Council may authorize the use of force to maintain or restore international peace and security

Necessity:

- the use of force must be necessary to address a specific threat or aggression

Proportionality:

- the level of force used must be proportional to the threat or aggression being addressed

Ius in bello, “law in war”

- conduct of armed conflict, regulating the behavior of belligerents and protecting civilians and other non-combatants

Distinction:

- distinguish between military targets and civilian populations

- soldiers can only make war against each other — not against civilians

- you cannot destroy civilian targets — what ordinary people need in order to survive

- if you take things from enemy territory, you must pay for it

Proportionality:

- attacks must not cause excessive harm to civilians or civilian objects

Humanity:

- unnecessary suffering and cruelty must be avoided

- prisoners of war are civilians

- captured soldiers cannot be tortured or killed

- certain weapons cannot be used — e.g. chemical weapons

Neutrality:

- neutral parties are not to be involved in hostilities, and their territory and property must be respected

Destruction or removal of cultural heritage

- churches, mosques, places of religious worship

- museums

- archives

Previous wars …

- Napoleon goes shopping in the churches of Italy

- the English burn down the White House in 1812

Now consider as “barbarian actions” that are now allowed

Implementation

These conventions actually influenced the way wars were fought

- soldiers would carry legal manuals with them on the battlefield

- used — at least by the officers

- you could look up individual cases as they were happening

This legal order breaks down in the 20th century

- bombings in Hiroshima, Dresden

- the Blitz in London

- unbelievably “uncivilized”

- and Gaza today

Laws of war in Islam

- actually quite similar to the European tradition

Ius ad bellum

- permits the use of force in response to aggression or an armed attack against the Muslim community

- protection of the oppressed — regardless of their faith

- preservation of the Islamic faith

- pre-emptive strikes may be allowed under certain conditions to deter potential threats to the Muslim community.

Ius in bello

- Proportionality: The use of force should be proportionate to the threat, and excessive or unnecessary harm should be avoided.

- Combatants must distinguish between military targets and civilian populations

- The wounded, sick, and prisoners of war must be treated humanely

- Protection of religious institutions and the environment

- Protection non-military infrastructure vital to the civilian population

- The importance of ethical conduct during warfare, including treating enemies with respect

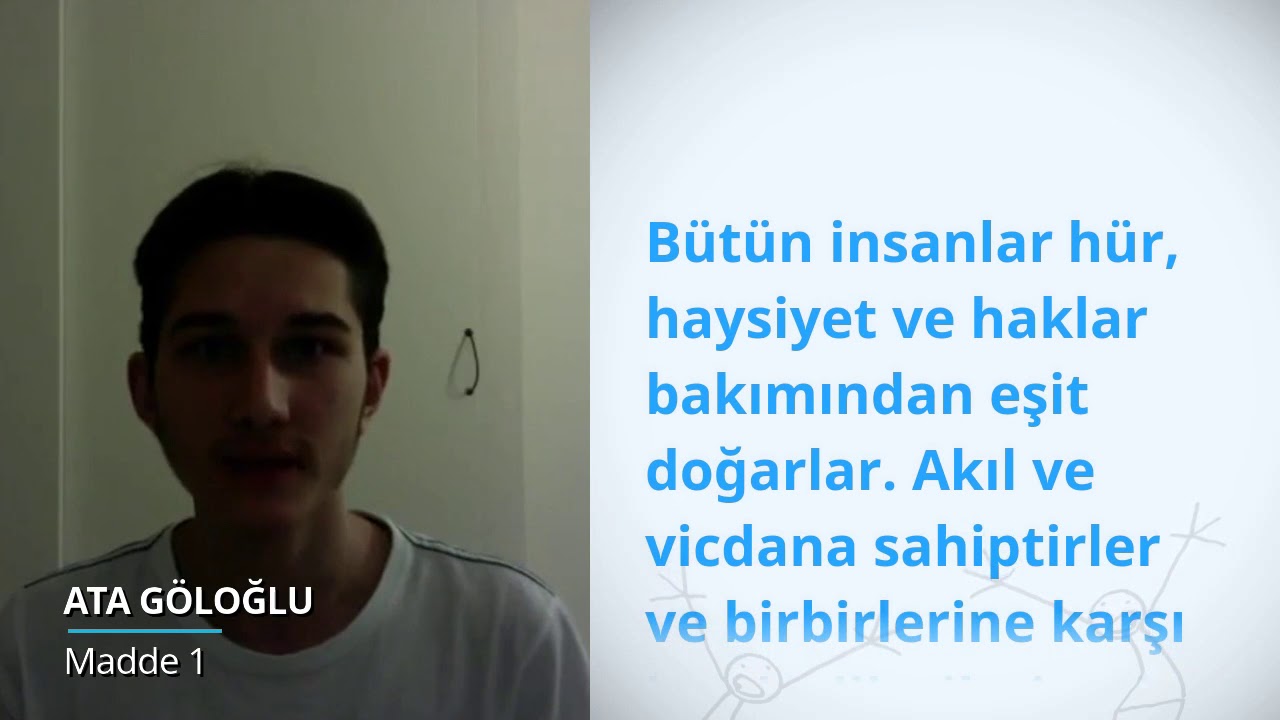

United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948

- foundation for international human rights law

- in Turkish

Origins:

The atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust

- need for a global consensus on fundamental human rights and values

- prevent future atrocities and promote peace.

Eleanor Roosevelt, the former First Lady of the United States, was appointed as the chair of the UNCHR

- over two years, they debated and negotiated the content of the declaration

- working to achieve a universal consensus on fundamental human rights principles

30 articles outlining a broad range of human rights

- including civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights

- the right to life, liberty, and security of person; freedom from torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment; freedom of thought, conscience, and religion

- the right to work and education

- and the right to participate in the cultural, social, and political life of one’s country.

Return of natural law?

Universality

- both natural law and the UDHR emphasize the universal nature of human rights

- human rights apply to all people, regardless of nationality, race, religion, or any other status

Inherent rights

- certain rights as inherent to all human beings, such as the right to life, liberty, and security of person

Moral foundation

- there is a moral foundation for human rights, which can be traced back to the natural law tradition

Higher law

- serves as a higher law that transcends national boundaries and provides a framework for evaluating the legitimacy of national laws and policies

Same problem as before — nature speaks too quietly

- what is the source of the law?

Cultural imperialism?

Critics argue that the UDHR’s emphasis on individual rights and liberties may not be universally applicable or acceptable in non-Western cultures, which often prioritize collective rights, duties, and social harmony

- positive vs negative rights — freedom from vs. freedom to

cf. US violation of prohibition of torture

Responsibility to Protect, R2P

First introduced in the 2001 report by the International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (ICISS)

- endorsed by the United Nations General Assembly in 2005

Three main pillars:

- the primary responsibility of each state is to protect its population from mass atrocities. States must prevent, mitigate, and address these crimes within their own borders.

- The international community has an obligation to assist states in fulfilling their responsibility to protect their populations.

- If a state is unable or unwilling to protect its population from mass atrocities, the international community has a responsibility to take collective action in a timely and decisive manner

Debate and controversy

- potential misuse of the norm for political purposes

- questions about its effectiveness in preventing and addressing mass atrocities

- what is left of the idea of sovereignty?

ICC, International Criminal Court

an independent, permanent international court that investigates, prosecutes, and tries individuals accused of committing the most serious crimes of concern to the international community

- genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression

- Israeli politicians and Hamas fighters under indictment

- international arrest warrants

Origin:

Established in Rome in 1998

- after receiving the required 60 ratifications

Work:

Based in The Hague, Netherlands

- can only exercise its jurisdiction when national courts are unable or unwilling to prosecute individuals accused of committing grave international crimes

Achievements

Investigations and cases:

- opened investigations into situations in several countries, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, the Central African Republic, Sudan, Kenya, Libya, Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Georgia, Bangladesh/Myanmar, and Afghanistan

First convictions:

- in March 2012, finding Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, a Congolese warlord, guilty of conscripting and enlisting child soldiers

- the court has convicted several other individuals, including Germain Katanga, Jean-Pierre Bemba, Bosco Ntaganda, and Dominic Ongwen.

Victim participation and reparations

- the ICC has implemented various reparations and assistance programs for victims and affected communities in countries where the court has investigated or prosecuted cases

Limited cooperation from some states, resource constraints, and criticisms of its perceived focus on African situations

Binding on the members?

- binding on its member states

- in some cases, states have not complied with the court’s requests for cooperation, such as arresting and surrendering indicted individuals

- the court does not have its own police force and relies on the cooperation of states to enforce its decisions

Not members

For example

- United States, Russia, China, India, and Turkey. The reasons for their non-membership vary, but some common concerns or reasons include:

Reasons for not joining

- some countries are concerned that the ICC’s jurisdiction could infringe on their national sovereignty

- the ICC could be used for political purposes, selectively targeting certain individuals or countries based on political motivations rather than objective legal criteria

- perceived bias or inadequacy — too much focus on Africa

Alternative regional mechanisms

- prefer regional courts

Lack of consensus within the country

Read more about the ICC, the International Criminal Court, here:

- The International Criminal Court.

- Wikipedia, “International Criminal Court.”

- New York Times Archive, “International Criminal Court“

ICJ, International Court of Justice

The principal judicial organ of the United Nations

- established in 1945 by the UN Charter

- 15 judges, who are elected by the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council for nine-year terms

- located in The Hague, Netherlands

The ICJ has two main functions:

Settling legal disputes between states:

- territorial boundaries, maritime rights, treaty interpretation, and diplomatic relations

Providing advisory opinions

- opinions on legal questions submitted by authorized international organizations and UN organs

Main differences between the ICJ and ICC:

- the ICJ deals with disputes between states, whereas the ICC primarily focuses on individual criminal responsibility

- ICC focuses on specific crimes — genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes, and the crime of aggression

- all UN members vs. those who have ratified the Rome Statute

ECHR, European Court of Human Rights

The Council of Europe

Founded in 1949 with the primary aim of promoting democracy, human rights, and the rule of law

- separate from the European Union

- the Council of Europe has 47 member states

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

- UDHR is a declaration, which means it is not a legally binding treaty

- the ECHR is a legally binding treaty for the Council of Europe’s member states

The ECHR established the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which has jurisdiction to hear cases brought by individuals, NGOs, and states alleging violations of the rights set forth in the convention

- the court’s judgments are binding on the member states

- the UDHR, as a non-binding declaration, does not have a specific enforcement mechanism

The member states are expected to comply with the court’s decisions and take necessary steps to prevent similar violations from occurring in the future

- the vast majority of ECHR judgments are implemented by the member states, although there can be delays and challenges in some cases

Non-compliance

- Demirtaş v. Turkey: In 2018, the ECHR ruled that the pre-trial detention of Selahattin Demirtaş, the former co-chair of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), was a violation of his rights to free expression, liberty, and security. The court ordered Turkey to take necessary measures to put an end to Demirtaş’s pre-trial detention. Despite the ruling, Demirtaş remained in detention until his eventual release on bail in September 2021. In the meantime, the ECHR ruled in another case (Demirtaş v. Turkey No. 2) in December 2020 that his continued pre-trial detention was in violation of the convention and had a political purpose, ordering his immediate release. This judgment was not implemented until his release on bail in September 2021.

- Cyprus v. Turkey: In the 2001 case of Cyprus v. Turkey, the ECHR found Turkey responsible for numerous human rights violations following the 1974 Turkish military intervention in Cyprus, including violations of the right to life, the prohibition of inhuman and degrading treatment, and the right to respect for private and family life. The court ordered Turkey to take measures to remedy these violations. Although Turkey has taken some steps to address the issues raised by the court, full compliance with the judgment remains incomplete, especially concerning the return of property to displaced Greek Cypriots and the establishment of an effective remedy for human rights violations in the northern part of Cyprus.

Turkey’s withdrawal from the Istanbul Convention

The Istanbul Convention, officially known as the Council of Europe Convention on Preventing and Combating Violence Against Women and Domestic Violence, is a comprehensive human rights treaty aimed at preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence. Adopted by the Council of Europe in 2011 and opened for signature on May 11, 2011, the Istanbul Convention is the first legally binding instrument in Europe that specifically addresses these issues.

The Istanbul Convention is binding on its member states, which are required to adopt and implement measures to prevent violence, protect victims, and prosecute perpetrators. The convention covers various forms of violence, including physical, sexual, psychological, and economic violence, as well as stalking, female genital mutilation, forced marriage, and forced abortion or sterilization.

The implementation of the Istanbul Convention is monitored by an independent expert body called the Group of Experts on Action against Violence against Women and Domestic Violence (GREVIO). GREVIO evaluates states’ compliance with the convention through a reporting process, which includes reviewing national reports, conducting country visits, and engaging in a dialogue with the state under review. Based on its evaluation, GREVIO publishes reports with recommendations for states to improve their implementation of the convention.

Turkey was the first country to sign and ratify the Istanbul Convention in 2011 and 2012, respectively. However, on March 20, 2021, Turkey announced its withdrawal from the convention through a presidential decree. The decision was met with widespread criticism and protests within Turkey and abroad.